RIDE FAIR (Javier Lovera), 7 minutes; THE GIG IS UP (Shannon Walsh), 88 minutes. Both films available Thursday (April 29) at 10 am to May 9. hotdocs.ca

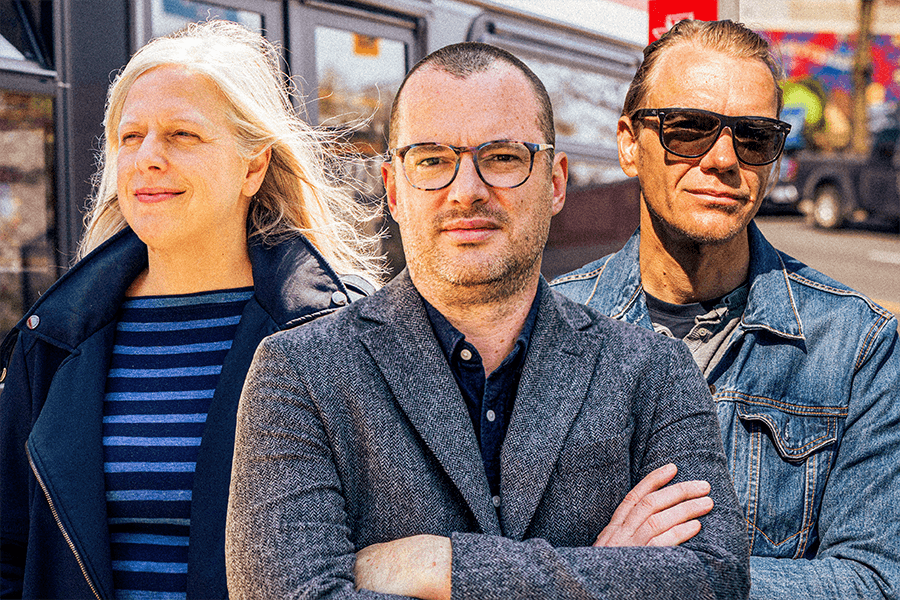

In the short documentary Ride Fair, JJ Fueser, Brendan Agnew-Iler and Thorben Wieditz meet virtually to discuss how private tech companies are increasingly becoming entwined in public policy.

The trio have successfully taken on tech giants Airbnb and Google-owner Alphabet, but their next target is perhaps trickier – Uber.

In a scene from the film, the trio throw ideas back and forth about how to enact genuine change, suggesting education and public policy targets that would contribute to further regulations for the ride-hailing app.

“The decisions that are being made by our government to enable these companies are not in the best interest of the public,” Wieditz tells the camera.

“It really takes an extraordinary amount of mobilizing and work in the community to make sure that the public interest is at the centre of policy making,” Fueser adds.

Directed by Javier Lovera, the documentary is part of a series called Citizen Minutes premiering at Hot Docs. It profiles Agnew-Iler, Fueser and Wieditz’s coalition RideFairTO (ridefair.ca), a group of transit advocates, environmentalists and gig workers who are pushing the city to regulate Uber and other ride-hailing companies.

RideFairTO already has two public policy wins. In 2017 under the name Fairbnb, the group lobbied for stricter regulations for short-term rental company Airbnb and similar platforms. Last September, new regulations came into effect in Toronto that require short-term rental operators register with the city and ban operators from listing properties on short-term rental sites that are not a principal residence. The goal was to crack down on illegal “ghost hotels” and free up long-term rental housing.

Members of the group were also part of the wider #BlockSidewalk opposition to Alphabet’s proposed Sidewalk Labs “smart city” on the waterfront, an initiative privacy watchdogs argued turns cities into “corporate surveillance states.”

Ride Fair is one of a handful of titles focusing on the gig economy at this year’s Hot Docs Festival. While Ride Fair focuses on the fight to regulate ride-hailing companies in Toronto, the feature-length documentary The Gig Is Up zooms out to examine gig work in a global context and localized campaigns to get gig workers classified as employees. (Another film screening at Hot Docs this year, The Big Scary “S” Word, profiles a couple, one working as a Lyft driver, who turn to socialism after realizing that capitalism is leaving them both in debt.)

The films arrive as public health data shows essential workers in Ontario are bearing the brunt of the pandemic’s third wave, prompting calls greater worker protections, including paid sick leave, to reduce virus spread. At the same time, Uber Canada is lobbying provincial governments to change employment law to create a new classification for app-based workers. The move would impact many of the 1.7 million gig workers in the country – or 8.2 per cent of the workforce, according to Statistics Canada.

And so, this group of Toronto activists is ready to fight for the third time.

A campaign against congestion

While Silicon Valley firms position themselves as disruptors, offering innovative high-tech solutions that make life more convenient, RideFairTO counters that companies like Uber use age-old lobbying strategies to deregulate and skirt employment protections. To persuade the public and policymakers, the group is arguing the wider well-being and development of Toronto is at stake.

“What kind of city do you want to live in?” Agnew-Iler asks. “If we’re going to put everybody in a private vehicle with a private driver, the streets are going to grind to a halt really fast. You’re going to have congestion everywhere, you’re going to have tons of pressure to build new road infrastructure. Or the solution that Uber would pitch, which is that they’re going to automate cars. Do you want to live in a city where every street has cars doing 100 kilometres an hour?”

Agnew-Iler previously worked as press secretary and senior advisor to Toronto mayor David Miller and was involved in a variety of transportation projects. So when he began thinking more about regulations for companies like Uber and Lyft, he brought the idea to Wieditz and then Fueser. RideFairTO officially launched in late 2020 after the trio had established alliances with a variety of organizations, including taxi companies, TTCriders, Toronto Environmental Alliance and CycleTO.

As RideFairTO, they are looking for resonant issues – like public transit and the environment – where they can make meaningful policy changes to push back against Uber.

“We felt that the province under this premier [Doug Ford] is never going to invite the labour changes that we want, so we focused on where we could win,” he says.

The team plans to pressure the city to determine a maximum number of ride-hailing vehicles allowed on the streets and put a cap on it, arguing that the cap is necessary in order to lower emissions and reduce congestion. Limiting cars on the road also means limiting the number of people working for Uber at one time, and Agnew-Iler says scarcity of cars will put upwards pressure on wages for workers.

Uber has sustained itself so far off of low-wage workers since people driving ride-hailing and delivery vehicles are classified as independent contractors. As such, they are not entitled to benefits under the Employment Standard Act, including breaks, a minimum hourly wage, sick days and other benefits.

“This campaign will let us tell a story about why a business model that relies on misclassification matters for everybody in Toronto on a pretty personal level,” Fueser explains. “If you want to take good, affordable transit, if you want relief from congestion and if you want Toronto to meet our air quality and emissions goals, you need to hear about this campaign.”

A 2019 report by the Ryerson Urban Analytics Institute found ride-hailing was contributing significantly to traffic congestion and tailpipe emissions in Toronto. It noted taxis are limited to around 5,000 cars, while private transportation companies (PTCs) have no cap and there are around 70,000 PTC licences currently issued in the city. According to the report, vehicle traffic contributes up to 41 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions in Toronto, and while taxis have regulations requiring vehicles to be low-emission, hybrid, alternative fuel or accessible, PTC vehicles have no emission-focused standards.

“The environmental gains from approximately 5,000 emissions-efficient taxicab vehicles will be completely offset and reversed by the emissions from approximately 70,000 PTC vehicles that are not required to be fuel-efficient,” the report explains.

In a statement, an Uber Canada spokesperson said the company is working to become a zero-emissions platform by 2040. “Uber has made transit journey planning available, providing Torontonians with real-time information on public transit options in-app.”

The rep also said Uber is “committed to helping reduce individual car ownership and expanding transportation access, making cities much more livable.”

“When it comes to greenhouse gas emission reductions, it just seems that by allowing Uber to grow exponentially in the city, we undermine all other existing policy objectives that city council has voted on and supported over the last several years,” Wieditz says.

The campaigns aimed at Airbnb used a similar strategy.

“We were able to show that Airbnb undermines the housing market and has turned thousands of homes into what we call ghost hotels, that are not accessible to renters who want to live long-term in Toronto,” he says.

RideFairTO’s second strategy has been to look at the effect of ride-hailing on public transit, releasing a report in February that found the TTC was losing 31 million rides annually to ride-hailing companies, which equals a loss of around $74 million in revenue. The team’s campaign was compelling enough to convince the TTC to conduct a study in partnership with the city looking at the impact of ride-hailing on transit.

Wieditz wants governments and the public to reflect on the impact Uber’s business model is having on city life.

“On the surface, it seems like an efficient transportation option. You can get a ride within less than two minutes. But once you start peeling back the layers, you see this is possible because Uber is allowed to literally flood the city streets with idling and cruising private vehicles, ready to pick someone up at any given point in time,” he explains. “That business model is highly inefficient, and highly environmentally problematic.”

Fueser says one of RideFairTO’s goals is to make the “cost of convenience” visible to everyone. She wants to challenge the idea that Uber is somehow an “innovative” business model. “Using an app to provide a service just isn’t that innovative anymore, and they’re using a lot of very old-school labour relations tactics that are predatory in predictable ways,” she says.

A global view in The Gig Is Up

Labour relations in the gig economy are explored in a global context in The Gig Is Up, directed by Vancouver-based Shannon Walsh. The documentary profiles gig workers in the U.S., France, Nigeria, China and other countries who work for Uber, Lyft, Deliveroo and Amazon Mechanical Turk.

In the film, Walsh meets workers who are trying to make a living off of these platforms, but are faced with shrinking wages and the constant threat of being “deactivated.” Sidiki, an undocumented migrant worker in France who delivers food for UberEats, describes his job like this: “We protect the food more than our own lives.”

For example, if he delivers a drink to someone and a bit of coffee spills in the bag, the customer might complain to UberEats, which could deactivate his account “like you’re nothing,” he says. He shows Walsh’s camera a path he biked for a food delivery one day. “Seven kilometres… €5.54.” (About $8.30 CAD.)

Some drivers and delivery workers featured in the doc say they were making livable wages when they first joined an app, only to see earnings drop as the market became more saturated. Others discuss the constant, never-ending demands of a job that has been marketed as “flexibility.”

In one scene, a delivery worker for Uber and Deliveroo says she feels pressure to be overly polite out of fear someone will give her a bad rating and she’ll be deactivated. Another worker says that after accepting and then cancelling three orders in a period of three months, Uber penalized them.

Uber Canada tells NOW that drivers and delivery workers can accept and reject any trip or delivery request they receive, and stated that when it comes to customer complaints, it’s only in “extreme and rare instances” that there may be an investigation that could result in loss of access to the Uber platform.

“One thing that was really clear was that people’s experiences around the globe are more similar than different,” Walsh says. “We really wanted to make sure that we captured the kind of flattening of this global phenomenon, the way this kind of technology and platform-based apps are changing work.”

Walsh notes that even though task-based work existed before, these new platforms are different. “The reality of what it means to be tethered to an algorithm is something that a lot of us haven’t really considered. The idea that we’re actually losing people work through bad ratings,” she adds, “we’re not rating apps, we’re rating human beings.”

Exploitation becomes possible because of misclassification, something labour lawyers say is a tried-and-true method that has been used for decades to suppress worker rights.

Mary Gellatly, a lawyer at Parkdale Community Legal Services, compares Uber to the garment industry in the 1900s.

“Companies would pay people on a piece- rate basis and it was always a struggle to get paid enough for each piece of the garment that you worked on,” she says. “Of course, it was all subcontracted out – people doing garment sewing in their homes.”

Since Uber drivers aren’t paid by the hour, the company encourages them to be out in the city at all hours, since the more drivers on the road, the faster service will be – while still not paying them for time spent idling between passengers.

While the technology and business models are not innovative, Fueser says the way communications are weaponized against drivers, cities and governments is new.

“They mobilize the app to talk to passengers and drivers, to be able to constantly plant their message, their version of events, into those audiences and activate those audiences to communicate with decision-makers,” she says.

She says PR spin allowed ride-hailing companies to win a pivotal fight in California by passing Proposition 22, which created new “laws” for app-based workers instead of classifying them as employees.

The proposition doesn’t guarantee paid sick days, denies access to unemployment benefits and doesn’t allow workers to unionize. The ballot, backed by more than $200 million from Uber, Lyft, Doordash, Instacart and Postmates, was voted in after an advertising blitz that presented the proposition as one that drivers wanted, giving them “flexibility” and “control” over their own work hours and conditions. The proposition effectively rolled back the state law Assembly Bill 5, which would have classified gig workers employees.

Uber floats new labour laws in Ontario

As the public is focused on COVID-19, Uber is lobbying provinces to create a new labour category for app-based workers. The plan, called Flexible Work+, would allow workers to accumulate “benefit funds” that they could use for dental expenses, education and retirement funds, for example. These “self-directed benefits” would be based on hours worked so drivers could amass funds and “withdraw cash.”

An Uber Canada rep says 81 per cent of drivers are in favour of Flexible Work+, and prefer the independent contractor model over employment.

“All platform companies would be required to participate so that workers can build up benefits regardless of which app they might be using at any given time. Should this plan become the law in all of Canada, Uber alone would have to contribute over CAD $40 million to benefits funds annually,” the company said.

The second piece of the proposal involves “enhanced worker protections” via “additional training and tools to help keep workers safe and protected while driving and delivering.”

“This discussion is just starting and we look forward to conversations with provincial governments and industry on how best to implement benefits and protections to drivers and delivery people,” the company said.

Uber has said the company’s financial condition hinges on how drivers are classified. A 2019 U.S. Securities Exchange Commission filing states that Uber’s “business would be adversely affected if drivers were classified as employees instead of independent contractors… reclassification would require us to fundamentally change our business model.”

Wieditz says stopping the proposed legislative changes is vital for the future of workers everywhere.

“That’s what’s at stake in Canada if Uber is successful in convincing people that we should introduce a different labour category for workers that they employ,” he says. “Other industries will very quickly follow suit, and what we’ll see is a gigification of entire existing industries that right now have employees, and in many cases, unionized employees.”

Josh Mandryk,a lawyer at Goldblatt Partners who works on labour and worker rights issues, says passing new legislation to create an “underclass of workers” is worrying from a legal standpoint, as it could set a precedent for future cases. “Even if it doesn’t affect you now, you should understand that these types of changes could be coming for your work next,” he says.

RideFairTO hopes recent positive decisions – such as a 2021 court ruling in the UK that said Uber workers will be given worker status, including minimum wage – will be a wake-up call for Canada. In early 2020, the Ontario Labour Relations Board ruled that Foodora couriers were dependent contractors of the food-delivery company, allowing delivery people to unionize.

However, the company pulled out of the Canadian market and initiated bankruptcy proceedings.

Fueser says that if RideFairTO is going to win this battle like they won the last ones, activists need to assemble a “broad and politically diverse” coalition to push for change.

“With Airbnb, we were able to put together really broad, unusual alliances over a couple of basic principles. And I think that’s also what it’ll take,” she says. “As the companies try to cleave us apart, our work will be to unite us all around a certain set of public goods.”

Citizen Minutes producers Lisa Jackson and Lauren Grant discuss the series, and the production of Ride Fair, in the latest episode of the NOW What podcast, available on Apple Podcasts or Spotify or playable directly below:

NOW What is a twice-weekly podcast that explores the ways Torontonians are coping with life in the time of coronavirus. New episodes are available Tuesdays and Fridays.